We need to talk about leadership

Against a backdrop of unethical conduct, irresponsible leadership and distrust of authorities and institutions, there is a pervasive sense that we are not well served by our leaders. There is a sense that, too often, leaders are disposed to serve a narrow group of interests before the public interest. As a result, there is a yearning for a culture of leadership that serves the greater good.

However, a range of key questions persist. What is the greater good? What is leadership for the greater good? What are the collective responsibilities of those who manage, govern and lead the institutions of the government, public, private, and not-for-profit sectors? How should authorities behave in order to be perceived by the community as showing leadership for the greater good?

Despite the difficulty of defining the greater good and leadership for the greater good, it is critical to think and talk about these ideas and practices in the public domain as clearly as we possibly can. Only then will institutions, leaders, and the public be able to imagine, practice and sustain the leadership needed to ensure the long-term welfare and well-being of the general population.

What is the greater good?

The concept of the ‘greater good’—and its synonyms, the ‘public good’ and ‘common good’—has the quality of being familiar and commonplace. Yet, these concepts are difficult to define or articulate in a precise or comprehensive way.

Moreover, as observed by the philosopher Hans Sluga, the diverse conceptions of the good—such as justice, happiness, security, order, prosperity—and the variety of local, national or global communities for which the ‘good’ is sought militates against the identification of a single good. However, a promising candidate for the greater good, apt in the context of our complex societies and wicked social, economic and ecological challenges, is the well-being of the whole. Understood in this way, the greater good is more an umbrella term for several interlocking concepts and conditions that underpin the survival and flourishing of life.

Despite the complexity of the concept of the greater good, it is critical that the discussion about the greater good and leadership for the greater good moves into the public domain. It is also important that the discussion of these ideas, as well as our expectations of leadership for the greater good, are characterised by a degree of compassion in relation to the difficulty of actually practising leadership for the greater good, riven as it is with incompatible goals and tensions. Leadership for the greater good is essential, but paradoxical, and therefore not easy.

Moreover, leadership for the greater good takes many forms and its meaning and manifestation varies across contexts. Leadership for the greater good in the context of a crisis or disaster looks very different from leadership for the greater good in more peaceful times.

What is leadership for the greater good?

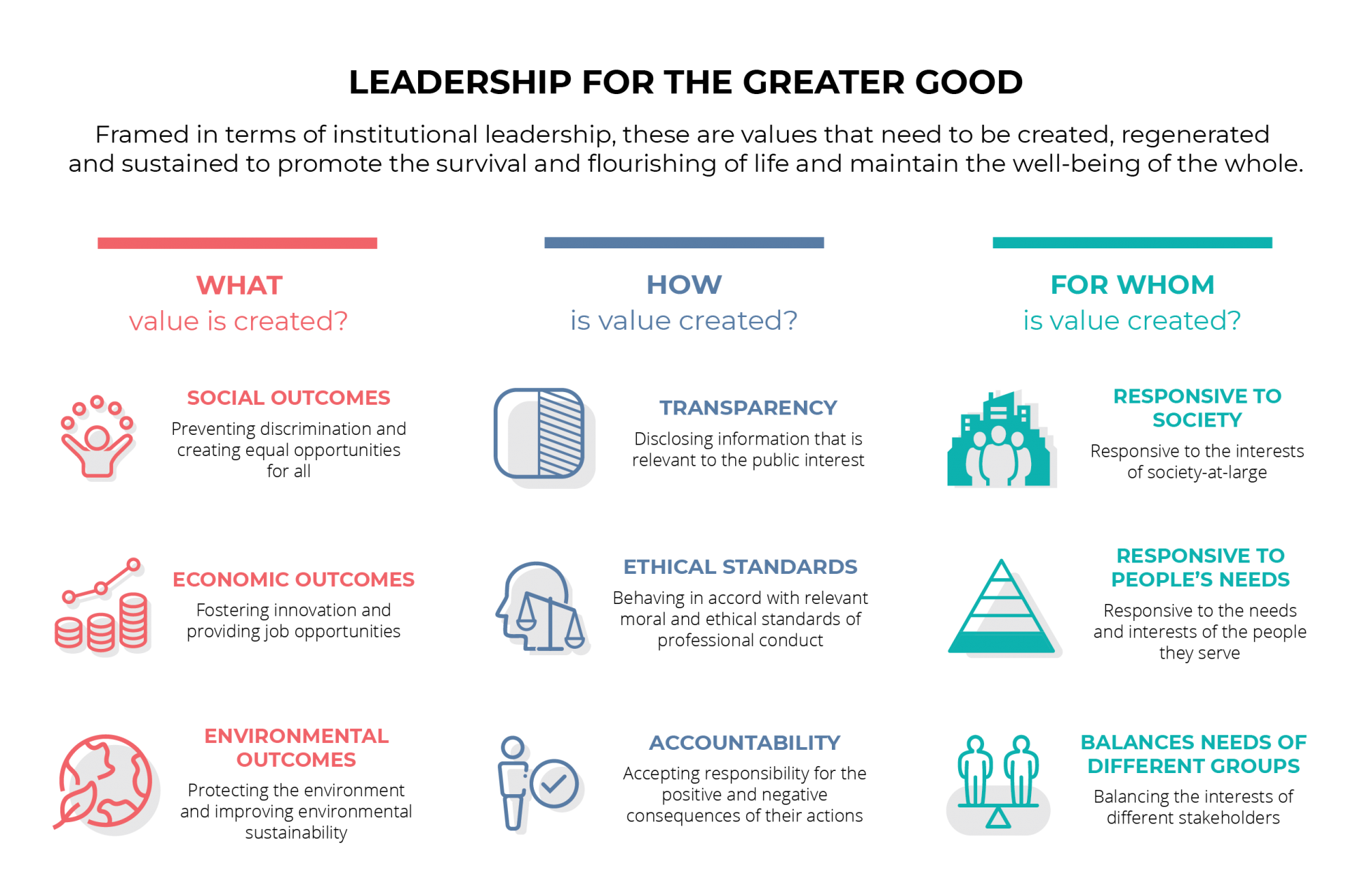

To render the concept of the greater good and leadership for the greater good less abstract, it is helpful to frame these ideas in more familiar terms. Specifically, it is useful to think about the greater good, and leadership in its service, in terms of ‘value’; namely, the types of value that needs to be created, regenerated and sustained in order to promote the survival and flourishing of life and to sustain the well-being of the whole.

This approach calls to mind the common, public and private goods that sustain collective well-being, as well as norms of distribution, pertaining to the stakeholders for whom value is created, and notions of ethics, which refers to the principles that inform value creation and distribution. In other words, this approach to thinking about the greater good calls attention to the types of value that we seek to create, how we create value, and for whom we create value.

Framed in terms of leadership, specifically institutional leadership, this approach to thinking leadership for the greater good draws attention to the types of value that institutional leaders seek to create, how they create value, and for whom they create value.

Understood in this way, the value-relevant outcomes of institutional behaviour allow inferences to be made about institutional leaders’ concern for, and stewardship of, the greater good. Moreover, because concern for, and stewardship of, the greater good is not the sole responsibility of any single institution, but all institutions whose actions have some bearing on it, leadership for the greater good transcends specific institutions and sectors.

The model of institutional leadership for the greater good that used in the Australian Leadership Index delineates these three aspects of leadership for the greater good and measures public beliefs about these aspects across the government, public, private and not-for-profit sectors.

Regarding the type of value, the ALI assesses public perceptions and expectations regarding the extent to which institutional leaders should create positive social, environmental and economic outcomes. Creating positive social outcomes includes preventing discrimination and creating equal opportunities for all. Creating positive environmental outcomes includes protecting the environment and improving environmental sustainability. Creating positive economic outcomes includes fostering innovation and providing job opportunities.

Regarding how institutional leaders create value, the ALI assesses public perceptions of the extent to which institutions are, and should be, accountable, transparent and ethical in their conduct. Accountability refers to the extent to which institutions accept responsibility for the positive and negative consequences of their actions. Transparency refers to the extent to which institutions disclose information that is relevant to the public interest. Ethicality refers to the extent to which institutions behave in accord with relevant moral and ethical standards of professional conduct.

Finally, with regard to the stakeholders for whom leaders create value, the ALI assesses perceptions and expectations of the extent to which institutions are responsive to the needs and interests of the people they serve (e.g., internal stakeholders like employees and external stakeholders like customers) and responsive to the interests of society-at-large. The ALI also assess perceptions and expectations of the degree to which institutions balance the interests of different stakeholders.

In sum, leadership for the greater good occurs when institutional leaders endeavour to create value for their stakeholders and society in a manner that is transparent, accountable and ethical.