Vlad Demsar, Swinburne University of Technology; Jason Pallant, Swinburne University of Technology; Melissa A. Wheeler, Swinburne University of Technology; Samuel Wilson, Swinburne University of Technology; Sylvia T. Gray, Swinburne University of Technology, and Timothy Colin Bednall, Swinburne University of Technology

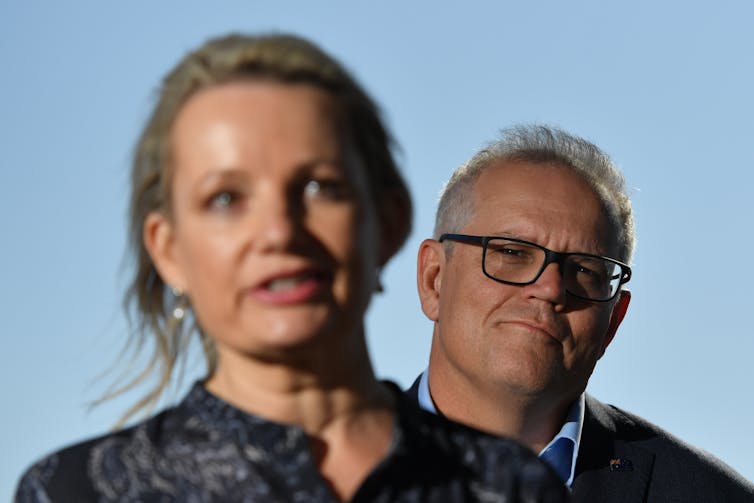

In recent months, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has faced pressure both domestically and internationally to do more on climate change. In contrast, state governments have been applauded for adopting more ambitious emissions reduction targets.

Data from the Australian Leadership Index suggests these differences may have electoral consequences. It found environmental outcomes increasingly shape how voters view their political leaders. And alarmingly for the Morrison government, the public has well and truly registered its lack of action on climate change.

In 2020, public attention on COVID-19 provided some cover for political leaders not acting on climate change. But from February to April this year, when climate issues rose to the fore, producing positive environmental outcomes became a key driver of public perceptions of political leadership.

As the next federal election looms, voters are watching closely to see whether the Morrison government’s environment and climate policies serve the public interest.

What is the Australian Leadership Index?

The Australian Leadership Index is a national survey which has been running since 2018. It seeks to provide a comprehensive picture of how perceptions of leadership change in response to events over time and across sectors and institutions.

Each quarter, the index surveys 1,000 adults to reveal how institutional leaders – those in government, private, public and the not-for-profit sectors – can show leadership for the greater good.

Such leadership is as much about process as outcomes. Given this, the survey measures public perceptions of the extent to which leaders try to create positive outcomes in three areas: social, economic and environmental. It also looks at perceptions of leaders’ transparency, ethical standards and accountability.

Among the questions asked of survey participants is whether state and federal governments are focused on producing positive environmental outcomes (such as protecting natural places and improving sustainability) and the extent to which this determines how favourably they view these institutions.

Who’s doing best on the environment?

On climate change policy, the Morrison government has opted to prioritise investment in low-emissions technology rather than introduce taxes or set emissions reduction targets.

In late April, the weakness of Australia’s national policies were laid bare during a global climate summit convened by US President Joe Biden. Australia was criticised before and after the summit for failing to set clear targets for emissions reduction.

This criticism did not go unnoticed by the voting public. Our survey showed from February to April 2021, the proportion of Australians who agreed the federal government was producing positive environmental outcomes declined from 38% to 25%.

The decline may also be linked to a major independent report by Professor Graeme Samuel in late January, which declared Australia’s environment was in a poor state and national laws protecting it were flawed and badly outdated.

The picture was different for perceptions of state governments. From February to April 2021, the proportion of Australians who believed state governments were producing positive environmental outcomes increased from 26% to 37%.

Australian states and territories have taken relatively ambitious action on climate change, including committing to net-zero emissions by 2050.

However, only around one-third of respondents believed governments at any level were focused on producing positive environmental outcomes. Clearly, even the states have more work to do in this area.

In the months since April, public attention has largely turned back to the COVID-19 pandemic, and scores on environmental performance reverted to previous levels. Last month, the proportion of Australians who agreed the federal government was producing positive environmental outcomes was at 37%. And it was 25% for state governments.

This reflects how national conversations about climate change and other environmental issues — including mainstream and social media and other forms of public debate – can shape voter opinions.

When people evaluated the overall leadership of governments in 2020, producing positive environmental outcomes had a 3% impact on their assessment. In January to April of 2021, this figure rose to 10%. This meant the environment became the third-largest driver of leadership perceptions, behind responsiveness to people’s needs (34%) and transparency (16%).

From May to June, however, the importance of environmental outcomes fell back to 3%. Again, this reflects the effect of media coverage in shaping voter attitudes to their leaders.

Keeping the environment in the spotlight

So what does all this mean? Governments wanting to be seen as good leaders must have strong, well-implemented climate and environment policies. And when media coverage and public debate is heavily focused on these issues, governments cannot easily brush them aside.

Concern about the environment is not guaranteed to sway a person’s vote. But our results suggest when public attention is focused on environmental issues, voters look to their leaders for an effective response.

It follows, then, that keeping climate change and the environment in the national spotlight will force governments to act with more urgency and serve the greater good.

Vlad Demsar, Lecturer of Marketing, Swinburne University of Technology; Jason Pallant, Senior Lecturer of Marketing, Swinburne University of Technology; Melissa A. Wheeler, Senior Lecturer, Department of Management and Marketing, Swinburne University of Technology; Samuel Wilson, Associate Professor of Leadership, Swinburne University of Technology; Sylvia T. Gray, Research Assistant and Casual Academic, Swinburne University of Technology, and Timothy Colin Bednall, Senior Lecturer in Management, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.