Written by Samuel G. Wilson, Vlad Demsar, and Melissa A. Wheeler.

The issue of public integrity has become increasingly prominent in recent years. As chronicled in myriad news stories and several reports into trust, accountability, public integrity, transparency, and corruption, government institutions are now widely seen as places of maladministration, ethical misconduct, and abuse of power. Although the issue of public integrity is germane to all levels of government, it is an issue of particular concern in the context of the federal government.

In light of growing perceptions of corruption in Australia, the recent decision by the federal government decision not to establish a federal integrity commission this parliamentary term, despite a promise in December 2018 to do so, and a forthcoming federal election, it is timely to review what the Australian Leadership Index has discovered about community perceptions of federal government integrity since the beginning of Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s leadership of the federal government in August 2018.

As outlined by the South Australia’s Independent Commission Against Corruption, public integrity comprises several core themes: public trust, public interest, morality, impartiality, transparency and accountability. The Australian Leadership Index measures several aspects of public integrity, offering unique insight into perceptions and expectations of government integrity.

In this report, we analyse public perceptions and expectations of federal government integrity from October 2018 to December 2021, focusing on public perceptions of federal government leadership for the public good, ethics and morality, transparency, and accountability. The sample size for this period is 4,329 respondents, collected at a rate of approximately 300 respondents per quarter across all states and territories. Whereas Q1 refers to January-March, Q2 refers to April-June, Q3 refers to July-September and Q4 refers to October-December.

The rise and fall of public leadership

Those elected to public office are required to faithfully serve the public interest, prioritising public over private interests when performing their duties. In terms of public leadership, defined by Brookes and Grint (2010) as the collective leadership of public institutions that seeks to promote and deliver public value, the principle of public interest calls on leaders to serve the public good and to ensure that their institutions do so to the greatest extent possible.

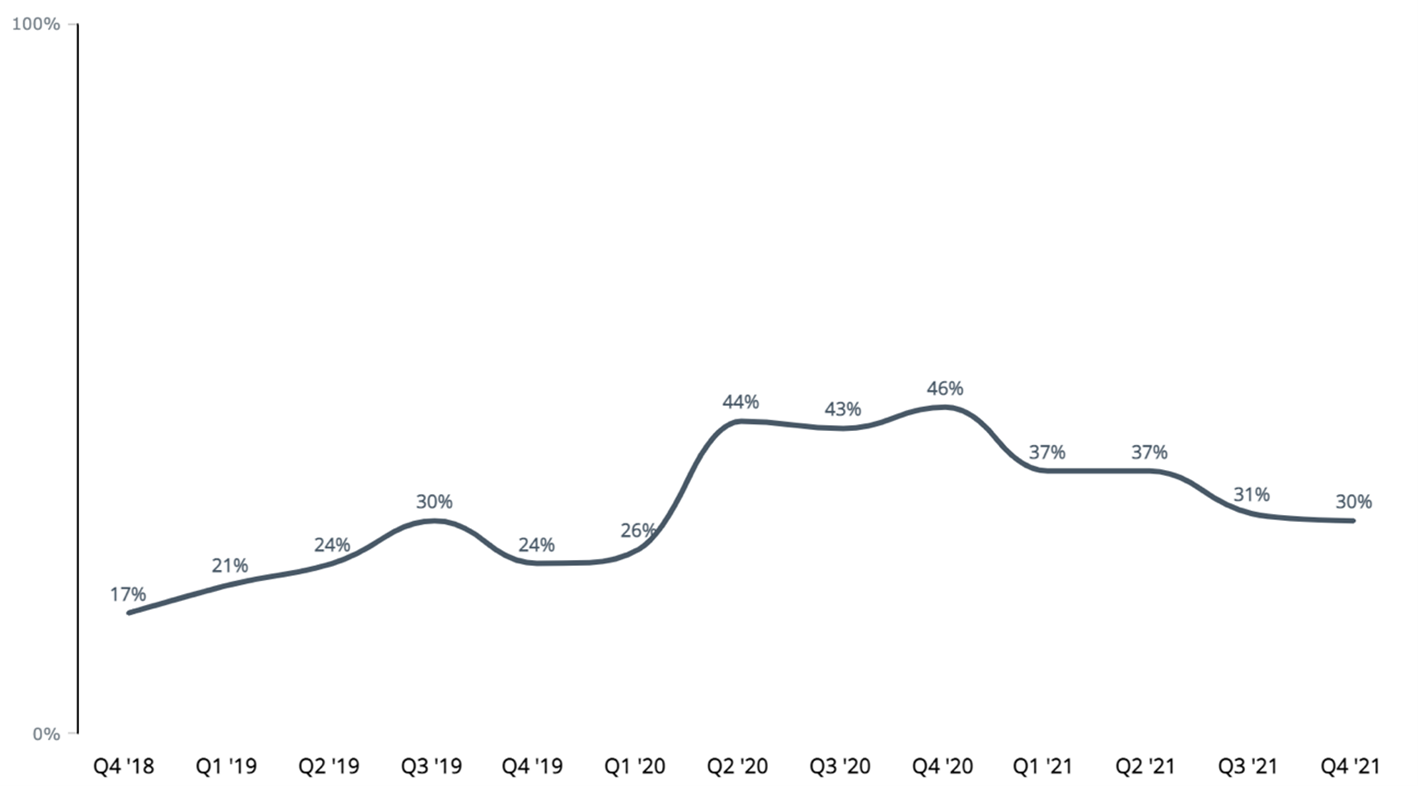

Using one of five response options—not at all, to some extent, to a moderate extent, to a fairly large extent, and to an extremely large extent—we asked respondents to tell us the extent to which the federal government demonstrates leadership for the public good. In Figure 1, we combine the proportion of those who judged the federal government to show leadership for the public good ‘to a fairly large extent’ and ‘to an extremely large extent’ to reveal the proportion of respondents who perceive the federal government as showing leadership for the public good.

As shown in Figure 1, public perceptions of the federal government fluctuated considerably between October 2018 to December 2021, rising and falling in response to crisis and self-inflicted political wounds. Within this timeframe, perceptions of federal government leadership for the public good were lowest when Prime Minister Scott Morrison came into office after years of political instability in the Liberal Party and federal government, with only 17% of respondents judging the federal government as showing leadership for the public good. Public perceptions of federal government leadership reached their height in late 2020 when 46% of respondents thought the federal government as showed leadership for the public good. However, these favourable perceptions eroded throughout 2021, reaching pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2021.

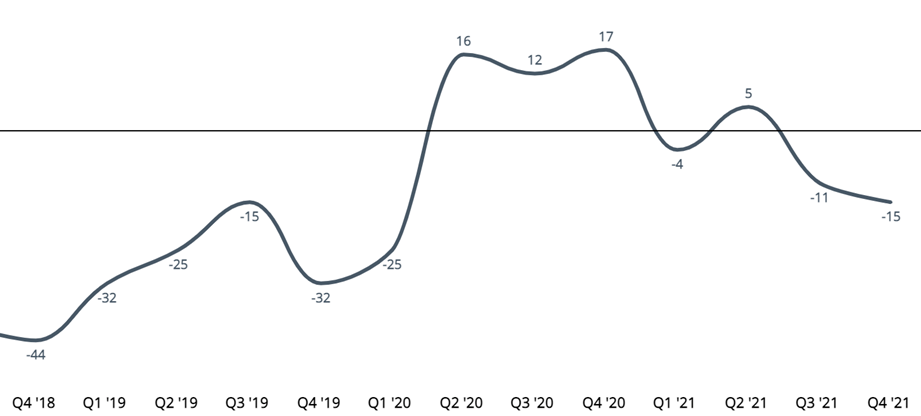

A more striking picture of public perceptions of federal government leadership is provided when ALI scores are charted. The ALI score is calculated in a similar way to the Net Promoter Score, a well-known and easily understood index ranging from -100 to +100. The ALI score for the federal government is calculated as the proportion of people who believe the government shows leadership for the public good to a ‘fairly large extent’ or ‘extremely large extent’ minus those who believe that the government shows leadership for the public good ‘to some extent’ or ‘not at all’. Positive scores indicate that the federal government is perceived as showing leadership for the public good, whereas negative scores indicate a general belief that the government does not lead for the public good.

As shown in Figure 2, in the final quarter (September-December) of 2018, the ALI score of the federal government was -44, climbing to a then high of -15 on the eve of the 2019/2020 bushfire crisis. The bushfires began threatening rural communities in September 2019. By December, the crisis had escalated, with out-of-control bushfires across multiple states. The federal government was widely perceived to have mismanaged this crisis, in terms of its lack of preparedness for the bushfires, under-resourcing of fire services, and its failure to respond to the warnings of fire chiefs. By the end of 2019, the ALI score for the federal government had plummeted to -32.

2020 was an eventful year for Australian governments, which commenced with the ongoing challenge of managing the 2019/2020 bushfire crisis, the “sports rorts” affair in January, and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March. By the end of March, public perceptions of federal government leadership were still dismal, reflected in an ALI score of -25 for the first quarter of 2020. However, unlike its response to the bushfire crisis, the federal government responded more swiftly to the pandemic, closing national borders to all non-residents in March 2020 and introduced a significant stimulus package. At the same time, a National Cabinet between the federal and state governments was formed, signalling greater cooperation between usually adversarial state and federal governments. However, 2020 was not scandal free: in September 2020, the Auditor-General revealed that the Commonwealth paid $30 million for a parcel of land later valued at only $3 million for Sydney’s second airport. Overall, in 2020, public sentiment towards the government was positive, reflected in ALI scores of between +12 and +17.

The public approval enjoyed by the government collapsed dramatically in 2021. The troubles of the government began early with strong criticism for failing to tackle a culture of sexual assault and bullying in parliament, as revealed in a major report. In early March 2021, thousands of people marched at rallies around Australia to protest against gendered violence. Former Attorney-General, Christian Porter, announced in December 2021 that he would quit politics at the election after a tumultuous year in which he sued the ABC for defamation after he identified himself as the subject of a report concerning historic sexual assault allegations and refused to reveal who was helping him pay, through a “blind trust”, his legal bills. In addition to this, in June 2021, the Australian National Audit Office found the that the federal fund for commuter car parks and road intersections didn’t award money on merit. The government also sustained heavy criticism the for the slow roll-out of coronavirus vaccines. In this context, the ALI score for the government fell from -4 in the first quarter 2021 to -15 by year’s end.

Ethics and morality: honoured more in the breach than observance

Morality is another important aspect of public integrity and relates to the imperative for public leaders to consistently act in line with ethical principles or values that are accepted by the public, such as honesty and fairness.

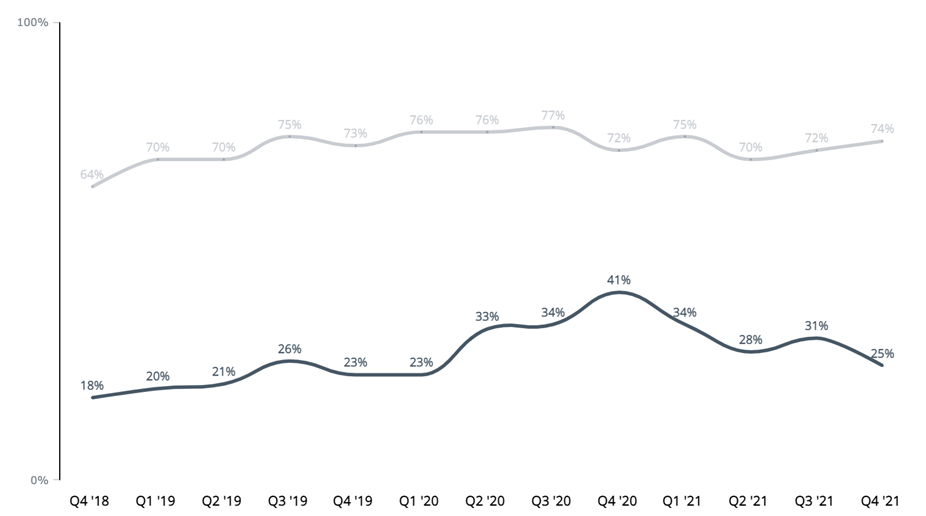

Using one of five response options—not at all, to some extent, to a moderate extent, to a fairly large extent, and to an extremely large extent—we asked respondents to tell us the extent to which the federal government behaves ethically, which we define as behaving in accord with relevant moral standards of professional conduct. In Figure 3, we combine the proportion of those who judged the federal government as ethical ‘to a fairly large extent’ and ‘to an extremely large extent’ to reveal the proportion of respondents who judge the federal government as highly ethical.

As shown in Figure 3, public perceptions of the ethical standards of federal government have fluctuated throughout the tenure of the Morrison government, improving steadily throughout 2019, with some regress during the 2019/2020 bushfire crisis, and rising markedly during the pandemic in 2020. At the height of public opinion towards the federal government in late 2020, 41% of respondents judged the government as highly ethical. However, in the context of the events of 2021, public perceptions of government ethicality declined precipitously. Averaging across 2018-2021 reveals that only about a third of respondents judge the federal government as highly ethical, whereas two-thirds of respondents expect the federal government to conduct itself in a manner that this highly ethical. This represents a profound gap between public perceptions and expectations that appears to be widening with time.

Transparency: out of sight but not out of (the public) mind

A third critical aspect of public integrity is transparency, which relates to the imperative for public leaders and institutions to be open and transparent with information that is relevant to the public interest.

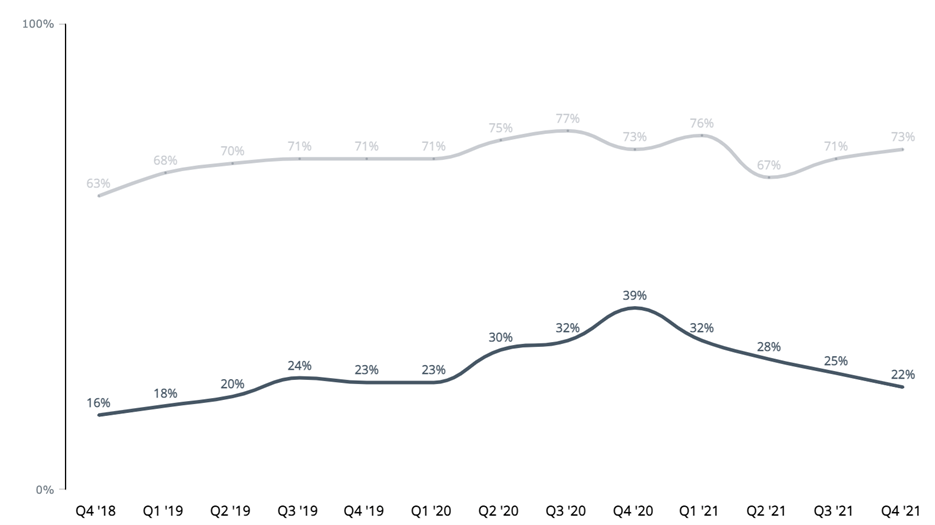

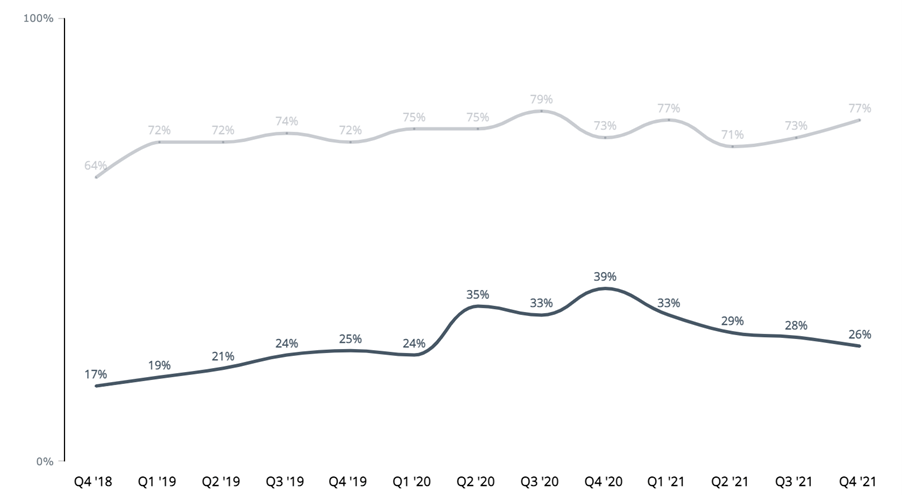

Using one of five response options—not at all, to some extent, to a moderate extent, to a fairly large extent, and to an extremely large extent—we asked respondents to tell us the extent to which the federal government is transparent, which we define as disclosing information that is relevant to the public interest. In Figure 4, we combine the proportion of those who judged the federal government as transparent ‘to a fairly large extent’ and ‘to an extremely large extent’ to reveal the proportion of respondents who judge the federal government as highly transparent.

As shown in Figure 4, public perceptions of government transparency are characterised by the same trends as seen in government ethicality, rising steadily from 16% of respondents when Scott Morrison came into office in late 2018, reaching a high of 39% in late 2020, and declining markedly throughout 2021. As observed with public perceptions of the morality of federal government, perceptions of government transparency are characterised by the persistent gap between public perceptions and expectations of government transparency. Despite a narrowing of this gap in 2020, thanks entirely to a lift in perceived performance rather than a lowering of community standards, the perception-expectation gap become increasingly pronounced throughout 2021.

Accountability

A final and vital aspect of public integrity is accountability, which relates to the need for public leaders to report on how public resources are used, how they perform their duties, and to be answerable for failing to meet performance standards.

Using one of five response options—not at all, to some extent, to a moderate extent, to a fairly large extent, and to an extremely large extent—we asked respondents to tell us the extent to which the federal government is accountable, which we define as the extent to which the government accepts responsibility for its actions and the consequences of its actions. In Figure 5, we combine the proportion of those who judged the federal government as accountable ‘to a fairly large extent’ and ‘to an extremely large extent’ to reveal the proportion of respondents who judge the federal government as highly accountable.

As shown in Figure 5, public perceptions of government accountability are characterised by essentially the same trends as seen for government ethicality and transparency, rising steadily from 17% of respondents in late 2018, reaching a high of 39% in late 2020, and declining throughout 2021. As observed with public perceptions of the government ethicality and transparency, perceptions of government accountability are marked by the persistent and now growing gap between public perceptions and expectations of government accountability.

The sorry state of public integrity

As demonstrated in this analysis of community perceptions of federal government integrity, the government performs poorly on all aspects of public integrity measured by the Australian Leadership Index: public interest, ethics and morality, transparency, and accountability. Over the three-year timeframe of this analysis, and across all metrics analysed, only about a third of respondents judged the government as behaving in a manner that accords with the public integrity principles of public interest, ethics, transparency, and accountability. Notably, when these results are interpreted in the context of community expectations, it is apparent that Australians have found the government wanting on all aspects of public integrity. On the face of it, this pattern of results suggests the public has lost faith that the system serves their interests.

Although the large and growing gap between community perceptions and expectations of public integrity is troubling, not least because of the corrosive effects of declining public integrity on the institutional foundations of democracy, the gap between what is (community perceptions of government) and what could or should be (community expectations of government) also presents opportunity. As noted by the American systems scientist, Peter Senge, the gap between what is (truth) and what could be (aspiration) constitutes a type of creative tension that can be harnessed in the spirit of vision, imagination, and regeneration. At best, addressing the complex and seemingly entrenched public integrity issues revealed by the Australian Leadership Index can provide a rallying point for a new generation of public leadership to renew the institutional foundations of Australian democracy.