Written by Timothy Bednall, Melissa Wheeler, Samuel Wilson, Sylvia Gray, & Vlad Demsar.

Much has been written about supposed intergenerational differences in attitudes across Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z[1], but is there any evidence to suggest that people of different ages have different expectations concerning leadership? We sought to answer these questions with data collected from the Australian Leadership Index.

How have generational differences been characterised?

Looking first at intergenerational differences in the workplace, compared to older generations, Millennials have been characterised as skilled in the use of digital technology and motivated by the alignment of company values with their own personal values but unwilling to perform boring or repetitive tasks and more motivated to engage in job-hopping.

However, among rigorous studies that make intergenerational comparisons, there seems to be very little evidence that such attitudes are substantially different across generations. Some authors have also observed that attributing an important issue to a single cohort (e.g., burnout in Millennials) does a disservice to other age groups affected by the same issue.

Claims regarding intergenerational differences must also be viewed with a healthy sense of scepticism. In addition to the arbitrary way in which generations are defined, there is considerable variation within each cohort in terms of attitudes, beliefs and values. That is, there is little consistency between individuals within the same generation.

On the other hand, there are real differences in the formative experiences and the challenges faced by each generation that may give rise to differences in attitudes and behaviours. For instance, Generation X observed the rise of greater workforce participation of women, the rise of home computing and the Internet, and greater attention paid to high-profile corporate scandals.

Millennials face a greater prospect of insecure work (possibly unfairly characterised as job hopping), an increasingly unaffordable housing market, and the burden of repaying government debt well into the future. According to the Australia Talks dataset, most younger people believe that they will be worse off than their parents’ generation.

There is also a sense that younger generations are more concerned with environmentalism, particularly with the threat of climate change. For instance, as a teen activist, Greta Thunberg is renowned for her protests and challenges to world leaders for their lack of action on climate change.

In Australia, teenagers won a landmark class action lawsuit against the federal government over their approval of a coal mine, with the court ruling that the environment minister had a legal duty to protect younger people by not exacerbating climate change. These environmental concerns make sense, given that these generations will likely live long enough to witness many of the serious effects of environmental degradation.

What the data says…

Because of these differences in the circumstances in which each generation grew up, we sought to investigate whether these differences would lead to differences in the way that each generation perceives leadership. Specifically, we investigated which aspects of leadership were most strongly related to perceptions of the greater good. We performed this analysis across all sectors, including the government, public, private and not-for-profit sectors using all data collected to date.

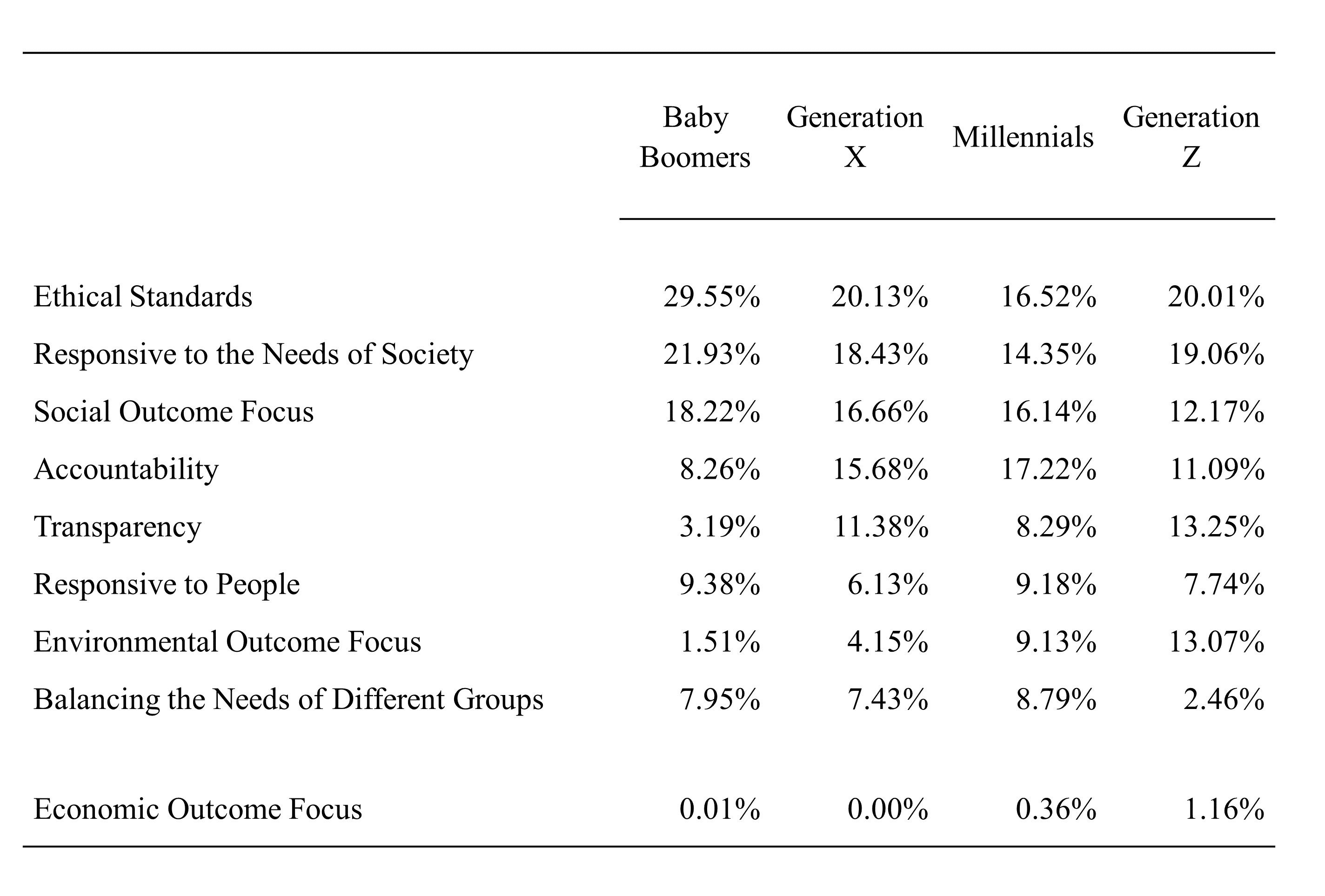

The most striking result from this analysis is that there are more similarities than differences between the generational cohorts. All groups consistently reported ethical standards, being responsive to society’s needs, and a focus on achieving social outcomes as the strongest drivers of leadership for the greater good. Similarly, people of all ages tended to rate a focus on economic outcomes as being less important. These priorities appear to be consistent across all age groups.

The age cohorts begin to differ in terms of their expectations regarding the conduct of leaders. Baby Boomers are primarily focused on ethical standards, whereas other characteristics appear to be regarded as less important. This difference may be due to the way in which ethical standards are interpreted; for instance, they may be seen as fairness by some people and respect for tradition by others.

In contrast, younger generations (Generation X, Millennials and Generation Z) appear to have broader expectations of their leaders, with much greater importance placed on accountability and transparency. Thus, these younger generations appear to have a greater interest in the systems and institutional governance practices that surround leaders.

Another substantial point of difference is the importance placed on achieving environmental outcomes. This aspect is least important for Baby Boomers in forming impressions about leadership for the greater good. And, as expected, this aspect becomes progressively more relevant for younger generations, with Generation Z placing the greatest importance on environmental outcomes.

Overall, while many of the leadership aspects are regarded with the same level of importance, there are some marked differences between generations. Younger Australians may be more concerned with transparency and accountability, possibly due to the rising reporting of scandals and the ease of accessing news on social media through any Internet-enabled device. With respect to the environment, younger generations appear to be tired of waiting for current leaders to address climate change, which will arguably affect them and their children more.

Relative importance of Factors associated with Leadership for the Greater Good

Footnotes

[1] In this article, we use the terms “Baby Boomer” to refer to post-war children born between 1946 to 1964, “Generation X” to refer to people born between 1965 to 1980, “Millennial” to refer to people born between 1981 to 1996, and “Generation Z” to refer to people born after 1997.